Over decades, antibodies have established themselves as a key therapeutic modality for a wide range of diseases. But antibodies as they are found in nature did not evolve to be used as drugs, says James Lazarovits, co-founder and CEO of Archon Biosciences. These proteins became drugs because scientists co-opted them to do things.

One of the limitations of currently available antibodies is the therapeutic window, which is the dose range within which a drug achieves its therapeutic effect without also causing dose-limiting toxicity. Lazarovits describes this window as the interplay between how much of the drug gets to where you want it to go versus how much goes where you don’t want it to go (thereby causing toxic effects). The technology of Archon changes the size and shape of an antibody, adjusting how a therapy gets where it needs to go in the body, what it does when it gets there, and whether or not it stays there. The Seattle-based startup emerged from stealth this past week with $20 million in funding for R&D of what could become a new class of antibody drugs.

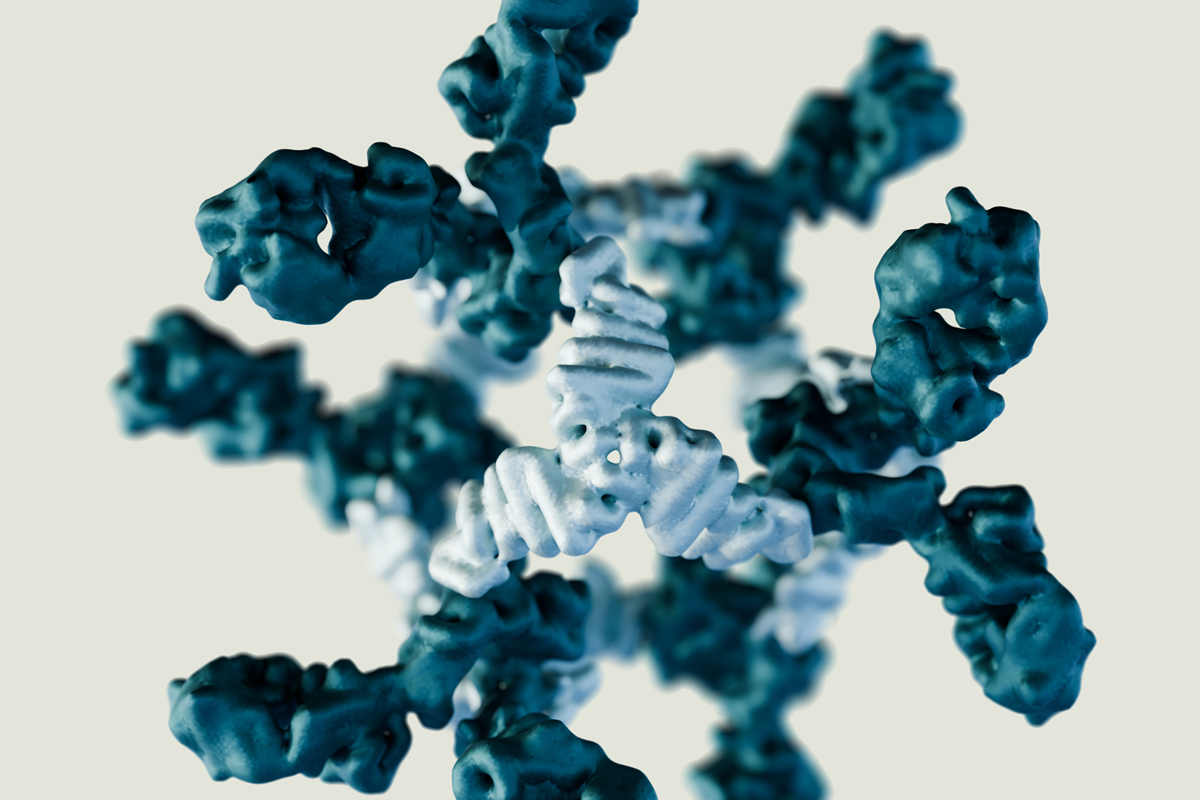

The field of antibody drug R&D includes efforts in multivalency, which is the ability to bind to multiple sites on the same target, and multispecificity, which is binding to two or more different antigens. These antibodies can be good for certain application, but not as good for others, Lazarovits said. Rather than engineering an antibody by altering the order of amino acids that make up a protein or adding different arms or multiple binding domains, Archon designs antibodies in a way that controls their structures. Archon calls its drugs antibody cages, or AbCs. These antibodies are made in a way that plugs into the established format for manufacturing antibodies, simply adding an additional work step at the end of the manufacturing process. But this additional step gives the antibody features it did not have in the first place.

An AbC offers tunability that is not found naturally in antibodies, Lazarovits said. More than just turning a target on or off, the AbC’s structure can adjust how much. Antibodies often require secondary signals to activate. While that’s achievable and controllable in a closed system, within a patient and across patient populations it become more difficult. Lazarovits said the structure of the AbC can autonomously activate pathways without needing something to happen elsewhere.

“The structure that we make changes how we actually activate the biology of a cell surface,” he said. “It’s not whether the antibody binds the target, it’s how it binds to the target.”

The Archon technology comes from the University of Washington’s Institute for Protein Design, which is led by David Baker, the professor of biochemistry awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work in computational protein design. Computational protein companies that have spun out of the institute include vaccine developer Icosavax, which was acquired by AstraZeneca last year for $800 million up front, and A-Alpha Bio, whose technology for analyzing protein-protein interactions has landed partners such as Bristol Myers Squibb.

Archon co-founder George Ueda worked with Baker for more than a decade. Lazarovits said their research initially aimed to develop proteins that had never existed in nature. Then they aimed to design proteins with unique structures. From there, they aimed to see if those structures could do something.

Lazarovits entered the picture about five-and-a-half years ago bringing a background in antibody delivery. Baker gave both Ueda and Lazarovits faculty positions. Their research landed $7 million in grant funding to further develop what became the AbC platform. The scientists were able to generate preclinical data to show what problems these novel antibodies could address. This research was published in 2021 in the journal Science. Lazarovits said the research also helped the scientists understand what kind of capital would be needed to use this new antibody science to develop novel drugs. Archon was incorporated in early 2023.

Archon is not yet disclosing the therapeutic indications it is researching. But Lazarovits said the programs the startup has selected address well-characterized targets that have been elusive to the pharmaceutical industry. Based on preclinical research, Archon understands the contingencies for activating and deactivating its selected targets. What that could mean for an Archon drug is similar activity compared to an already available medication but fewer side effects, increased potency, or some combination of both, Lazarovits said. He added that the company is pursuing acute indications, not chronic therapies.

By focusing on well-known, sought-after targets that have remained elusive, the “check box” of data Archon needs is very standardized, Lazarovits said. The company knows the data it needs to collect and it knows what to show to demonstrate how its antibodies are differentiated. Knowing all of this at the outset means generating the data can happen quickly.

The startup’s strategy resonated with investors. Archon’s seed financing was led by Madrona Ventures, a Seattle-based venture capital firm that has invested in several artificial intelligence-enabled biotech companies, such as Ozette and Nautilus Biotechnology. Other participants in the Archon financing include DUMAC Inc., Sahsen Ventures, WRF Capital, Pack Ventures, Alexandria Venture Investments, and Cornucopian Capital. Lazarovits said the funding gives Archon a runway of about two years.

More than generating data to demonstrate the science of AbCs, Archon will use its new capital to build a business case. Eventually, the startup aims to strike up partnerships with larger companies, Lazarovits said. When that happens, he wants to have enough data to know which assets to partner out and which ones to keep in order to build value for the young company. Conversations with pharma companies and additional investors are already underway, Lazarovits said.

“Because this is such an amenable technology for partnerships, we’re getting our ducks in a row,” he said. “If you try to do everything, you’re going to do everything pretty poorly.”

Image: Archon Biosciences