That is the title of a fantastic editorial from Olivença et al. (2024). A lot of people when they look at pharmaceutical prices think they are ‘too high’ or ‘too low’. But the question is, too high or too low relative to what? What are our goals in pharmaceutical pricing. The editorial clearly articulates the issue as one of a market design problem. I have heard one of the co-authors (Dr. Lou Garrison) make this comment multiple times at conferences, but it is helpful to see this written down in print.

Of note is that the market exclusivity drugs enjoy covers just the manufacture of a specific product; competitors may arrive with competitor treatments and identical generic copies may arrive after market exclusivity ends.

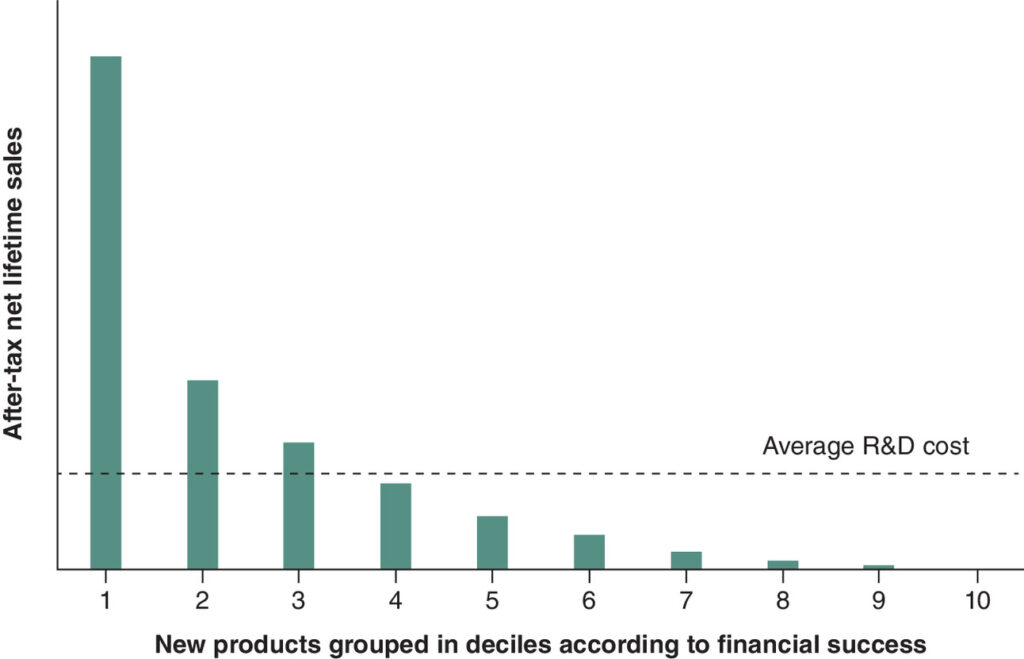

The value of this monopoly power is limited by market competition and time. This leads to a market framework that promotes medical innovation by offering potentially large but uncertain returns for high-risk investments, while using competition to regulate prices in the later stages of the product lifecycle.

The article begins by arguing against setting drug prices just based on research and development (R&D) cost:

[Cost plus pricing]…not only fails to recognize riskiness of these investments and the irrelevance in this market design of the costs of any specific product, but also the difficulties in identifying relevant failed products and in measuring their costs. Furthermore, this perspective would fail to convey the true value of novel medicines for patients and society, and thus stifle innovation by sending no signals of value to investors in the highly risky field of drug development.

The article argues against price setting such as those argued by Bernie Sanders among others:

Notably, Senator Bernie Sanders has recently asked Novo Nordisk for the R&D costs of semaglutide, a treatment for obesity. It is imperative that we communicate that using R&D costs to determine pricing is flawed and instead focus should be made on estimating the full value that a medicine provides to patients, their families and society. The ‘blockbuster model’…which relies on the revenues of successful drugs to cover the costs of the many failed attempts, is often misunderstood or overlooked in discussions about drug pricing and regulation. Of course, companies can still make profit on a ‘marginal’ product if the revenues cover the marginal R&D cost and costs of production and distribution; but a company needs a few products averaging multiples of average R&D cost to cover the failed products.

The figure below summarizes the blockbuster model.

A very interesting and clearly articulated editorial throughout. Read the full piece here.